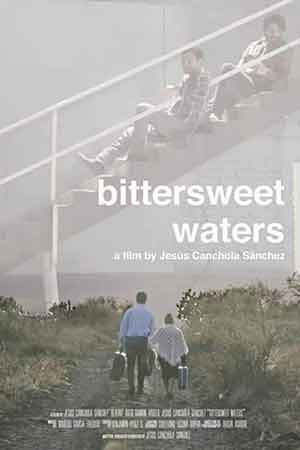

Bittersweet Waters (2019): Secret lovers in a small Mexican village

Bittersweet Waters (2019) – A quiet gay drama soaked in dust and shame

“Bittersweet Waters” (2019) is one of those quiet rural dramas that looks simple on the surface – a few adobe houses, a dusty road, a boy building a house brick by brick – but underneath it is full of secrets that could get people killed. Atl lives with his grandmother in a small Mexican village, carrying the legacy of a dead father, a poisonous mother and a love that has no right to exist in a place where everyone knows everyone – and pretends to know everything.

Atl – a soft boy in a brutal place

Atl is the kind of character you recognize immediately if you’ve ever grown up in a small, tight community. He works, he keeps his head down, he looks after his grandmother, he builds a house that is supposed to be his way out. On paper, he is the “good son”. In reality, he is just trying to breathe.

His relationship with Diego is not some shiny movie romance – it’s the kind of bond that grows in the shadows: shared beers, stolen glances, and that heavy mix of friendship, desire and fear. They’ve been together since they were teenagers, and by now their love feels as inevitable as it is impossible. Atl doesn’t dream of changing the whole world; he just wants the right to exist without being burned at the stake by his neighbors.

Diego – cowardice dressed up as tradition

Diego is the textbook closeted man in a macho culture. He wants everything: his boyfriend, his pregnant fiancée, his reputation as a decent straight guy. When he tells Atl that they can both get married – “If we’re both married, nobody can say anything” – you can almost hear the mental gymnastics snapping in his head. For him, marriage is camouflage, not commitment.

The film is at its strongest when it lets us sit inside Atl’s point of view while Diego pretends that nothing between them has to change. Diego keeps promising that “everything will stay the same”, but every new step toward his “normal life” pushes Atl further toward the edge. Their dynamic hurts because it is so familiar: one man ready to risk everything, and the other terrified of risking anything.

Dolores and Juanita – women trapped in someone else’s war

Dolores, Diego’s fiancée, is not a villain; she is a woman trying to hold on to the little bit of dignity and security life is offering her. She is pregnant, she wants a home, a husband, a future where people stop laughing at her behind her back. When she starts to suspect what is really going on between Diego and Atl, the film shifts into something darker – jealousy mixed with humiliation and raw survival instinct.

Juanita, the housemaid who moves between homes and secrets, becomes the accidental witness to everybody else’s lies. She knows more than she wants to, and the film uses her beautifully as a quiet moral mirror: she sees how unfair it all is, but she also understands exactly how dangerous this truth can be.

The mother, the grandmother and inherited violence

Atl’s mother is pure bitterness in human form – a woman who sees her son not as a person, but as a tool and a wallet. She manipulates him with guilt, with money, with threats, with the past. Every time she appears on screen, the air gets heavier. She is not “evil” in a cartoon way; she is what happens when frustration, patriarchy and greed stew for too many years in the same kitchen.

On the other side is the grandmother, who represents tenderness, memory and a different kind of tradition. With her bedtime stories and small gestures of care, she is the only person who loves Atl without conditions. The contrast between these two women – one who destroys and one who shelters – is one of the most powerful threads in the film.

Slow pacing, heavy atmosphere

Bittersweet Waters is not a fast film. It takes its time, and sometimes maybe too much of it. Some scenes linger in silence and everyday chores – walking, cooking, building, carrying – until you feel the weight of this place in your bones. Viewers used to tight, polished queer dramas might find parts of it a bit contrived or melodramatic, but that roughness actually fits the story. This is not a polished world; it shouldn’t look like one.

The cinematography leans into natural light, worn-out interiors and dusty hillsides. The village isn’t romanticized; it’s beautiful and suffocating at the same time. The music and the recurring song about “agridulce agua” underline that feeling of love that tastes sweet in the mouth but burns on the way down.

“The sin is not loving – the sin is separating us”

The line that stays with you long after the credits is the idea that the real sin is not their love, but their separation. That’s the heart of the film: in a world obsessed with “respectability” and appearances, two men who genuinely love each other are forced into lying, violence and tragedy just to keep other people comfortable.

Bittersweet Waters (2019) – about”

“Bittersweet Waters” matters because it doesn’t talk about homophobia in a big city, with rainbow flags and loud slogans. It talks about the small, everyday cruelties of a rural community where gossip can kill, where land and inheritance are more important than happiness, and where a man will marry a woman he doesn’t truly love rather than admit who he is.

It’s a sad, slow, sometimes clumsy film – but it feels honest. If you’ve ever had to negotiate your own existence around family expectations, religion, gossip or “what will people say”, you will probably recognize yourself somewhere in Atl’s gaze. And that’s the real bittersweet water here: the taste of a love that is completely real, and a world that refuses to let it live.