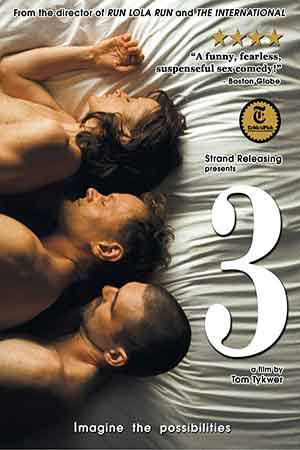

Three (2010): Love Doesn’t Choose Gender, It Chooses Chaos

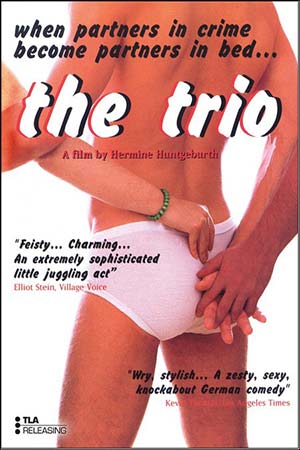

“Three” (or Three) is one of those German queer dramas that doesn’t need loud emotions or dramatic confrontations to get under your skin. Tom Tykwer, best known for films like “Run Lola Run” and “Cloud Atlas,” chooses a far smaller stage here just three people whose lives quietly collide-and somehow creates one of his most honest and intimate works.

At the center of the story are Hanna and Simon, a long-term couple in their forties who live together, share a life, and yet somehow stopped truly seeing each other. Their relationship isn’t falling apart; it’s simply drifting. They’ve become two people performing the idea of a couple rather than living it. Familiar conversations, half-hearted jokes, predictable frustrations-everything feels like an echo of who they used to be. Nothing is wrong, but nothing is alive either.

Then comes Adam, a warm and quietly magnetic researcher who enters their lives at the exact moment when they’ve both stopped expecting anything new. What they don’t know is that he will awaken something in each of them-separately, unexpectedly, and in ways that pull them out of their emotional hibernation.

The twist? Hanna and Simon both fall in love with the same man, without knowing the other is going through the exact same experience.

It’s a bisexual love triangle, yes, but “Three” refuses to turn it into chaos or jealousy. Instead, Tykwer approaches it with empathy and curiosity. There are no villains here, no dramatic showdowns, no accusations shouted across the room. Just three adults navigating desire, longing, and the quiet ache of realizing life didn’t turn out the way they hoped.

Hanna’s connection with Adam feels like rediscovering color after years of grayscale. She suddenly remembers what it felt like to be desired, to be surprised, to belong to a moment rather than a routine. Simon’s encounters with Adam are softer, almost shy-like someone who’s been holding his breath for years and finally exhales. Both relationships reveal different parts of who Hanna and Simon used to be, and who they could be again.

What makes “Three (2010)” especially refreshing is how effortlessly it handles sexuality. There’s no dramatic “identity crisis,” no big declarations, no need to categorize the characters. Their desires simply unfold. The film treats bisexuality with the same casual honesty as falling in love with anyone else. It doesn’t spotlight labels; it spotlights humanity.

Berlin itself becomes a subtle fourth character-elegant, slightly cold, yet full of quiet corners where life happens when no one is looking. Tykwer films the city with tenderness, letting it reflect the emotional states of his characters. The editing is clever and rhythmic, weaving their stories together in parallel, almost like a quiet dance they don’t realize they’re performing.

The humor in “Three” is understated but sharp. Moments of awkwardness, hesitation, or unexpected delight arrive in the most human ways. You smile not because the film tries to be funny, but because it captures the strange, messy truth of adult life-how desire appears at the wrong time, how people hide behind routine, how a single encounter can pull years of emotional dust into the air.

As the triangle deepens, the characters are forced to confront the emotional truths they’ve been avoiding. Illness, grief, longing, fear-they’re all present, but never exaggerated. Instead, they push the characters toward a quieter, braver form of honesty. The film suggests that reinvention isn’t always dramatic. Sometimes it’s simply a moment where someone admits what they need.

“3” isn’t a story about betrayal. It’s a story about rebirth. About love that refuses to fit into tidy boxes. About connections that arrive when you least expect them. About the courage it takes to stop pretending and start feeling again.

If you’re looking for a thoughtful, mature, queer European film-one that explores sexuality, identity, and midlife longing without clichés or sensationalism “Three” is a beautiful, slow-burning experience. It lingers long after the credits roll, not because of its twists, but because it gently reminds you how unpredictable the heart can be.

And as for the ending? Well… let’s just say happiness can have more than one shape.